Presentation of Severe Spasticity

Spasticity is classically defined as a motor disorder characterized by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) that results from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex. In the past, spasticity, tonic stretch reflex, and velocity-dependent hypertonia were terms used interchanagably to refer to spasticity.1

The clinical features of spasticity are recognizable and include1,2:

Clinical Features of Spasticity1,2

High muscle tone

Characteristically affects the antigravity muscle groups

- In the arms, tone is usually high in adductors of the shoulders, flexors of the elbows, wrist and fingers, and pronators of the forearm (excessive flexion of the fingers and adduction of the thumb results in characteristic clenched fist with “thumb in palm” deformity)

- In the legs, high tone is particularly prominent in adductors of the hips, flexors of the knees, and plantar flexors and invertors of the ankle

Varies with the speed of movement (the faster the stretch, the greater the resistance)

- Resistance is felt as a catch after an initial few degrees of movement and then builds up until it suddenly gives way (clasp-knife phenomenon)

Clonus

Involuntary rhythmic contractions triggered by stretch that can interfere with walking, transfers, sitting, and care

Spasms

Sudden involuntary movements that often involve multiple muscle groups and joints in response to somatic or visceral stimuli

Spastic dystonia (hypertonia)

- Tonic muscle overactivity without any triggers owing to the inability of motor units to cease firing after a voluntary or reflex activity; results in characteristic limb postures and contractures

- The inability to relax the muscles; a form of efferent muscle hyperactivity dependent on continuous supraspinal drive to spinal motor neuronsthat is different from spasticity and is difficult to assess without surface electromyography3

- Clinical features of velocity-dependent hypertonia may be different if the cause is spasticity or spastic dystonia; spasticity features habituation of of tonic stretch reflex, while this feature is replaced by a reflex facilitation in spastic dystonia3

Spastic co-contraction

Inappropriate activation of antagonistic muscles during voluntary activity due to lack of reciprocal inhibition causing a loss of dexterity and slowness of movements

Patients presenting with spasticity should be assessed for history, progression of symptoms, neurological conditions, evaluation of triggers, and impact on daily living.2 Various procedures and assessment scales may be used.

But what makes spasticity severe? Severity should be evaluated in terms of functional limitations to a patient. Intensity of spasticity should take into account the clinician’s, patient’s, and caregiver’s perspectives. Severe is best described as how problematic the spasticity is to the patient/caregiver rather than a just a numerical rating on a spasticity assessment measure.3

Even seemingly mild degrees of spasticity can lead to a profound inability to perform basic activities of daily living

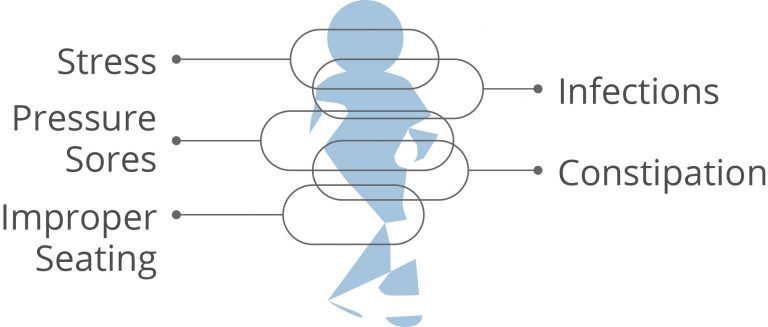

Symptoms of spasticity can worsen gradually over time and become problematic, particularly if they lead to increased pain, involuntary movements, loss of movement control, muscle weakness, deterioration of mobility, increased care needs, and sexual dysfunction.2 This may occur because of physiologic (visceral, somatic, or noxious stimuli) or psychologic (stress) triggers (see figure below).

Triggers of Severe Spasticity

Certain triggers can cause spasticity to worsen or become severe.2 Some of these triggers include2:

- Skin conditions (ulcers, ingrown toenails, boils, skin infections)

- Visceral conditions (constipation, urinary tract infection, urinary tract calculi, pain during menstruation)

- Devices (improper seating, ill-fitting orthotics)

- Drugs (rapid withdrawal of antispasticity medications)

- Other factors (stress, infections, injury, deep vein thrombosis)

Signs and symptoms of severe spasticity may not be the same from one patient to the next nor stay the same for a given patient over time. Patients may experience spasticity in one or several locations or their symptoms may be constant or be triggered by certain events.1 Furthermore, episodes of spasticity can fluctuate throughout the day; some patients may experience their worst spasticity in the middle of the night, whereas others may experience it in the middle of the afternoon.4

Referral to a physician who manages spasticity should be considered if a patient has new onset spasticity, spasticity that worsens rapidly without triggers, or new neurological signs.2

It is mandatory that all patients, caregivers, and treating physicians receive adequate information regarding the risks of treatment with intrathecal baclofen. Instructions should be given on the signs and symptoms of overdose, procedures to be followed in the event of an overdose, and proper home care of the pump and insertion site.

- Marinelli L, Curra A, Trompetto C, et al. Spasticity and spastic dystonia: the two faces of velocity-dependent hypertonia. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2017;37:84-89.

- Nair KP, Marsden J. The management of spasticity in adults. BMJ. 2014;349:g4737.

- Saulino M, Ivanhoe CB, McGuire JR, et al. Best practices for intrathecal baclofen therapy: patient selection. Neuromodulation. 2016;19(6):607-615.

- Bhimani R, Anderson L. Clinical understanding of spasticity: implications for practice. Rehabil Res Pract. 2014;1-11.